It’s DBIR season once again, and, as usual, the Verizon team has produced a detailed and comprehensive (and humorous) exemplar of statistical cybersecurity analysis and reporting. Last year, we noted that the data breach landscape was largely static from 2022 to 2023: threat actors were doing what worked and did not seem to find any reason to change that, especially in terms of phishing and credential stuffing. Unfortunately, this largely seems to be the case yet again. The MOVEit vulnerability and subsequent fallout plays a prominent role in the numbers and discussion this year, but the use of stolen credentials hasn’t gone anywhere.

For Basic Web Application Attacks, the section summary lays it out clearly: “Threat actors continue to take advantage of assets with default, simplistic and easily guessable credentials via brute forcing them, buying them or reusing them from previous breaches.” (2024 DBIR pg 42). While ransomware deployment dominates the System Intrusion attack pattern, credentials often play a critical role as well which we will discuss in more detail below.

Here in 2024, it remains pretty clear: stolen credentials are a consistent and continuous threat to organizations, and favorite trusted tool of malicious actors across many attack patterns. Let’s take a look at some of the details, and what organizations can do to protect themselves against ending up as a statistic in next year’s DBIR themselves.

If there’s one immutable fact about cybersecurity, it’s that the threat landscape is constantly evolving…except when it isn’t. Hackers (and security researchers) are always discovering new vulnerabilities, and developers are always releasing patches to fix them, but hackers by and large aren’t really motivated by the thrill of hunt (spoiler: it’s still the money), so most abide by the old “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” adage (DBIR pg 18). Luckily for them, users and organizations continue to demonstrate little interest in addressing some of their most prominent security gaps- namely, weak passwords and phishing. No matter how well the sysadmins keep machines and networks patched and updated, the old specters of password reuse and weak passwords can undermine all their work in the time it takes to make a single authentication request.

One of the great features of the DBIR is how they leverage the VERIS reporting system and data standardization to incorporate and analyze information from large, varied, and constantly changing army of contributors and data sources. One highly visible shift this year is the increase in breaches caused by internal actors or users, mostly due to “miscellaneous errors” like ‘misdelivery’ of communications. The authors attribute this to the increase in onboarding of mandatory reporting contributors, which means we’re seeing new legislation and regulations around breach disclosure in action. It may be still unclear whether more stringent rules around breach disclosures will have any effect on improving organizational cybersecurity, but at least this suggests we’re able to get a better look at what’s actually going on. Even though many breaches may not be the result of cybercrime, the end result for the user can still be damaging, and this data should be taken very seriously.

However, for the scope of this review, we are primarily concerned with external malicious actors, and their use of stolen credentials. Authentication remains a highly susceptible attack surface, and at Enzoic we want to understand threat actor behavior so we can ensure our products stay always on the cutting edge of account protection and breach prevention.

“Credentials are a core component of compromising organizations”

– 2024 DBIR pg 43

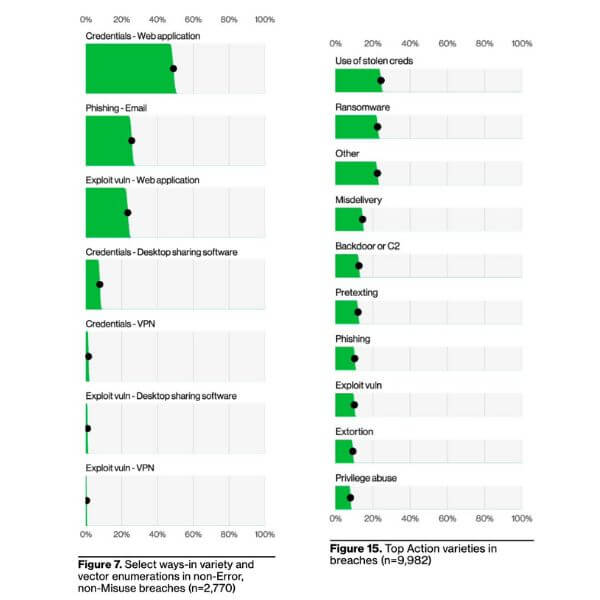

This year we saw “exploitation of vulnerabilities” claw back some ground from last year, largely thanks to the MOVEit vulnerabilities mentioned before, but “use of stolen creds” is still the top ‘Action’ taken by threat actors in data breach incidents (If this sounds like it was copied and pasted from last year’s report, well, it probably could have been…we’re running out of ways to say it). Mere repetition doesn’t really do this statistic justice at this point, and the DBIR authors helpfully presented another angle on actions in the report introduction this year. Below are two of the figures from the report to help explain: on the left, we have the “Top Action Varieties in breaches (n=9,982)” (Figure 15, DBIR pg 18), and on the right we have a subset of the most popular actions overlaid with popular vectors1 (Figure 7, DBIR pg 12).

Looking at the left chart (Figure 15), we can see that hackers have a wide range of tools, and like to use all of them to some degree. This speaks to the fact that cyberattacks are not typically a single action- rather they are a whole ‘chain’ of actions linked together to gain access to a system- not just a single technique applied to a single attack surface, or vector. So in any given attack, many ‘actions’ will be used across multiple ‘vectors’- and we get a closer look at this connection in the above chart on the right (Figure 7). We can see that credentials used against a web application is far and away the most popular action/vector combo, and that threat actors will generally opt for credentials over exploiting software vulnerabilities: in each of the 3 vectors, web applications, desktop sharing software, and VPNs, the use of credentials is over twice the frequency of vulnerability exploitation.

The message is clear: compromised credentials must be addressed as the first line of defense in any organizational security posture. Threat actors aren’t going to go in through a window when the front door is essentially unlocked.

“…there are a lot of things we don’t know about these credentials: Where do they come from, how did they get here and will we ever know the full story?”

– 2024 DBIR pg 43

Last year, the 2023 DBIR mentioned that it wasn’t clear where all the stolen credentials actually came from- a seemingly straightforward question, but deceptively slippery to answer. The query is recapitulated this year (see above quote), and accompanied by some interesting details from their investigation into infostealers as a source of stolen creds. They reported collecting over a thousand credentials per day over a two-day sample period, of which 65% were posted “less than one day from when they were collected” (pg 45). This underscores the vulnerability of users to infostealers, but doesn’t quite speak to the scale out there: so far in 2024, Enzoic has collected over 130,000 credentials per day from raw infostealers logs- and much, much more than that from aggregated lists traded by threat actors on various platforms.

Still, this is only a fraction of the over 10 million credentials/day that Enzoic processes, so where do all the others come from? Certainly, large amounts are repackaged data that threat actors trade, sometimes formatted in particular ways, or tested against particular websites or endpoints (e.g. confirmed valid accounts for Netflix), but much of it comes from the very data breaches that the DBIR is concerned with. Since the DBIR focuses on patterns and proportions, it’s not really possible to determine exactly how many total individual credentials were exposed in the breaches they report on, but as shown in the industry breakdowns, credentials are stolen in a non-trivial amount of breaches across all industries. Of course, most of these credentials are likely hashed, but this is sadly scant protection due to the high levels of weak passwords and password reuse. When threat actors attempt to crack hashes, the first thing they use is lists of passwords that have appeared in past breaches because, well, it works. People reuse passwords all the time, and this undermines the effectiveness of even the strongest hashing algorithms. So, threat actors get the exfiltrated user tables, crack many of the hashes, and post or sell the resulting credentials as easy-to-use “combolists”- files formatted to be easily used in automated tools for credential stuffing and account takeover.

While financial motivation is the underlying force in most cybercrime, reputation and credibility are necessary passports to gain trust and access to the communities where the most valuable data commodities are bought and sold. We can observe that threat actors not only value credential data for its usefulness in providing access, but that it is treated with precedence over other types of PII, and its sharing and possession can confer reputation increases. Like pirates parading their prizes, perpetrators proudly post proof of the purloined personal information, and thus bolster their standing within cybercriminal communities. This behavior, along with the data reported in the DBIR, make it extremely clear that stolen credentials continue to be an enormous threat. This is not exactly a revelation for security research, but the fact that users and organizations continue to be roiled by these attacks means that staying abreast of the stolen credential marketplaces, communication channels, and threat actor communities is absolutely paramount. As the DBIR points out on page 45, stolen credentials appear in the marketplaces within hours of their collection. Research and prevention solutions must take this timescale into account.

The DBIR breaks down the industry verticals by NAICS code, which they acknowledge has limitations in usefulness vis-a-vis cybersecurity postures, but it does help narrow the scope a bit- which can be helpful in trying to figure out how to prioritize for your organization and/or users. Cybersecurity is a never-ending story, and you’ve got to start somewhere. We certainly recommend that organizations find their most relevant industry to help identify their most vulnerable points, but it’s also important not to pigeonhole oneself, or accidentally overlook security holes due to taking too generic an approach.

One interesting change this year appeared in the “Retail” sector, where stolen credentials took the top spot of ‘most frequently breached data’ over payment card data. It’s no secret how popular credit card numbers are among fraudsters, and it seems pretty straightforward that online retail business would be one of the primary sources, thanks to the popularity of e-commerce among both consumers and threat actors like Magecart. It’s hard to tell exactly what drives these trends, as we don’t have large-scale access to the minds of the people committing cybercrime, and it could certainly be stochasticity showing up in the sampling, or ebb-and-flow of vulnerabilities moving through the global cybersecurity landscape. It does serve to bolster the argument that threat actors are ever more excited about stealing creds- which is ever-worse news for anyone who uses a password to login (i.e. everybody).

The main takeaway for any industry is to identify their potential attack surfaces and the most pressing actions that threat actors use against those surfaces, and prioritize those (without disregarding other security best practices- it’s always a balancing act). No matter how fast patches are applied, and how aggressive threat detection software, humans will always be the weak point in any organization. It’s a truly difficult problem that no one likes to acknowledge, but culture and training are some of the biggest cyberattack (and accidental breach) prevention tools that we have. Anyone is susceptible to being phished, pretexted, or credential stuffed, and it is imperative that organizations incentivize secure practices and behavior to protect their assets, brand, users, and critical infrastructure.

There is a huge marketplace of security tools and products out there, and it can be tough to know what is just smoke and mirrors, and what it is a crucial and effective service. MSPs and MSSPs can help SMB-size organizations take advantage of the best options out there, and services like Enzoic are designed to help security professionals reduce cognitive load and automate workflows while remediating insecure credentials with up-to-the-minute data.

1For example, the action would be “use of stolen credentials” and the vector might be a web application, or VPN software. The “vector” in this context is the actual attack surface that threat actors use to gain access, i.e. the door itself, not the key.

AUTHOR

Dylan Hudson

Dylan Hudson

Dylan leads the Threat Research team at Enzoic, developing and implementing cutting-edge threat intelligence infrastructure to help protect users and organizations from cyberattacks. When not at work, he can be found hiking and biking in the Rocky Mountains or playing traditional Celtic music on various stringed instruments.

Explore free for up to 20 users. Save hours of admin time and simply get started with a password monitoring solution.